木工:永野 智士(tomoshi nagano)

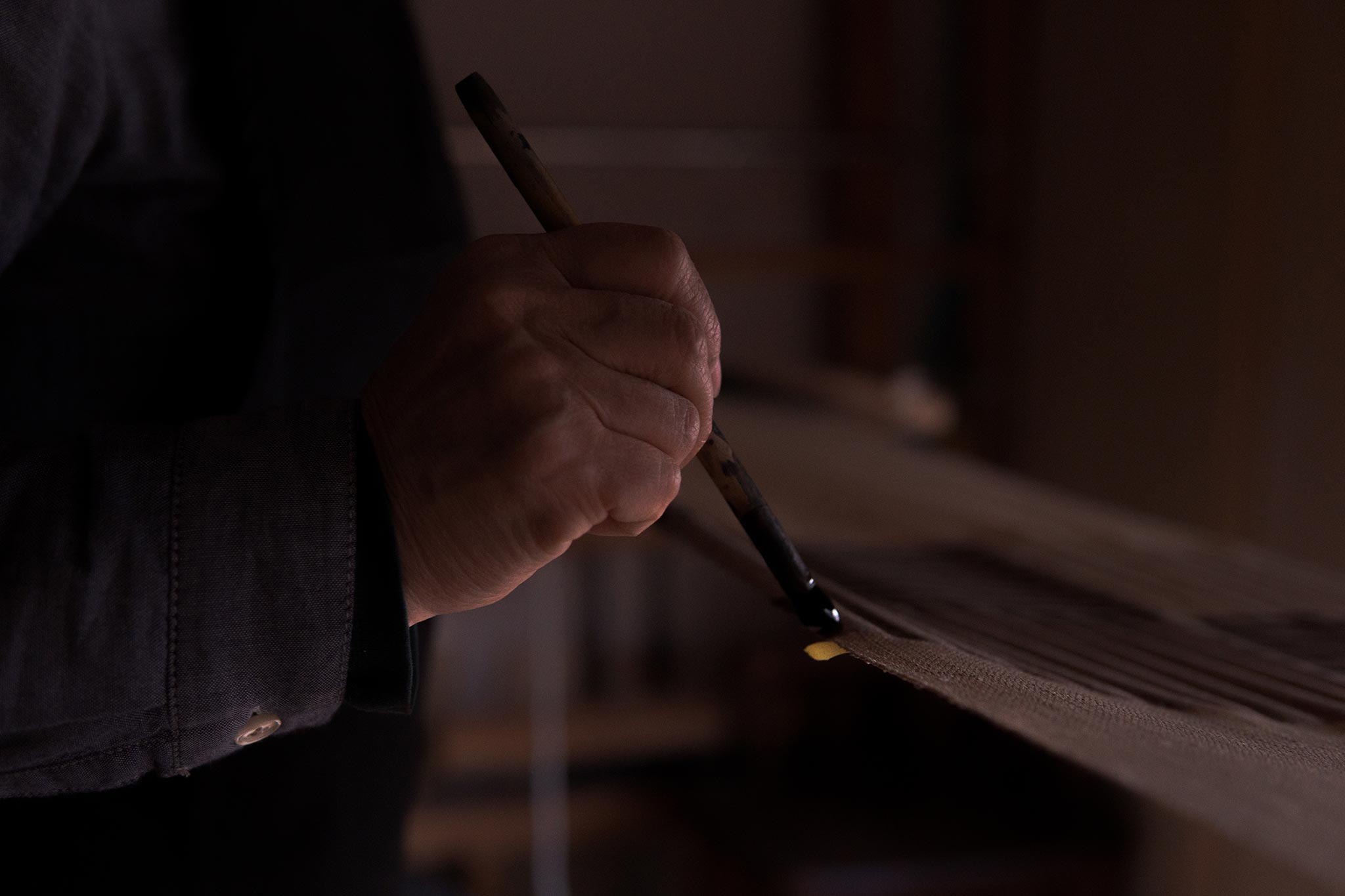

木工職人 永野 智士さんに、現在の木工の生業についてお伺いした最初の一言は「ものづくりにまったく興味がなかった」という意外な言葉からでした。音楽が好きで音響やレコーディングエンジニアになりたかった智士さん。音楽の専門学校を卒業後、たまたま知人の紹介でログハウス作りの手伝いをすることに。そこで出会ったログビルダーとの出会いが出発点となり「木工」一筋に導かれていくことになるのですから人生は面白い。

『その人は、設計士だけど常に現場にもいて自分で作業をする。根っからの大工というかビルダーだった。 彼の影響で一から十まで自分が携わるものづくりに憧れた。』という智士さん。

『ログハウスなので別荘地が多くて、何ヶ月間泊まり込みとか、一箇所で作り込むってことがまずないんですね。それが大変でした。それよりも一箇所でとどまったところでものを作るほうが性に合っていると思って、それで家具だったらある程度自分一人で作れるんじゃないか?と考えたんです。』

音楽から一転、家具作りに目覚めた智士さんは奈良にある木工所に就職。そこでは自社プロダクトの製作からデザイナー依頼の仕事など、家具作りの基本的な技術とノウハウを学びました。時間外は木工所の機械を自由に使っていいという恵まれた職場環境を活用して、休日は自身の家具作りの探求。設計から製作まで文字通り一から十まで自分一人で作っては試行錯誤する日々だったそうです。

日々家具デザインに没入していった智士さんは、次第に本場ヨーロッパの伝統的な建築や木工に惹かれるようになっていきました。

『その頃、フィンランドの「NIKARI」のカリ・ヴィルタネン※が日本に来てたんです。そのカリ・ヴィルタネンのパートナーが日本人の坂田ルツ子さんというフェルト作家さんで、母親の古くからの友人だったんですね。そこで日本にきた時にカリにぜひ会いたいとお願いしたんです。』

カリが来日した時に自分が作ったものを見てもらったという智士さん。その時は「もっとこうしたほうがいい」と、事細かく指摘され、自分の浅学さを痛感させられたそうですが、それから彼の木工人生を決定付ける出来事が起こることに。

『カリが帰国した後にパートナーのルツ子さんから電話がありまして、

カリが、“日本で会ったあの子、フィンランドに来るかな?”と、彼が主宰している「NIKARI」で働いてみないかと誘われたんです。即答で“ 行きます!”と答えましたね。』

それから5年、智士さんはフィンランドで「NIKARI」の一員として家具作りに携わります。「NIKARI」でずっと働きたかった。カリ・ヴィルタネンのものを作りたかったという智士さん。しかし5年後、帰国を決意。日本で独立して自身の家具作りをしていく道を選びました。同時に「NIKARI」製品の良さを日本でも紹介したい思いも強く、「NIKARI」を日本で生産するライセンス契約を結びます。こうして2010年、自身が生まれ育った場所、京都宇治に「永野製作所」を設立。自社オリジナルブランド「imous-design」と「NIKARI」の2本立ての木工家具の製作が始まりました。

※ NIKARI:家具職人カリ・ヴィルタネンが1967年に設立した家具メーカー。フィンランドのフィスカルス村を拠点とし、50年以上にもわたって、フィンランドの近代文化である木工と家具製作に先駆的役割を果たしてきた。

2012年、朝日焼 松林豊斎から、旅館にある茶びつ(蓋が盆になっているもの)を、和室でなくテーブルの上でも使える『茶箱』として、装飾的でなく家具的なモダンなイメージで作りたいと、智士さんに依頼しました。

この「茶箱」は栓(せん)という北海道の木を使っています。あまり聞き馴染みのない木材かもしれません。まるで北欧NIKARIの家具のような、それでいて和の直線美を感じる、智士さんならではの「茶箱」はどのように生まれたのでしょう。

『栓は木目に結構ばらつきがあるんですよ。正直あまり使いやすい木じゃない。なのでこの茶箱では木目選びと剥ぎ目にこだわりました。大きい木がないので薄い木を張り合わせるのですが、ぱっと見分からないでしょ? 剥ぎ目を自然に見せること、木の向きだったり色味を調整したりと、細部にこだわりました。でもそこを怠るとこういうシンプルなものはまとまらない。』

『一時栓が手に入りづらくなってきていて生産中止していたのですが、今はまた扱っている木材屋が見つかったので生産再開したところです。これが国産の木の難しいところですね。今まで伐採できていたものが、できなくなったり、いわゆる日本の広葉樹は植林されているものが少なくほとんど自生しているものになるので、土地開発で出たものとか、ヒノキ、杉の林に一緒に生えていたものとかに合わせて市場に出るので、ある時ない時がどうしても出てしまうんですよ。いったん刈ってしまうと最低でも50年とか100年かかる世界なのでなかなか次がない。』

『中心に隙間を入れている意匠にも意味があります。木というのは繊維の方向があり湿気によって伸縮します。これは「仕口(しぐち)」と言って、溝を掘っているんですよ。この溝の中で動けるようにしてあるんですね。だいたい1%の伸縮の余地をここで作ります。これは必然の機能なんですが、それをデザイン要素としてに落としこむことで同じスリットを入れていく意匠をつくりました。デザインにはすべて意味があり機能がある。これも「NIKARI」で学んだことなんです。』

『この「茶盆「は「茶箱」を製作して2、3年後に作らせていただいたものです。夏の器を置くのに使っていただけるように考えたものですが、持ち手の溝幅も最初は等間隔だったのですが、溝の下が広いほうが持ちやすいということで、この比率に落ち着きました。

デザインだけで考えると等間隔のほうが美しいのかもしれませんが、私の作るものは基本的に使い勝手、機能性にデザインが追従するという考え方です。』

フィンランド「NIKARI」で学んだ木工のノウハウを日本に持ち帰った智士さんですが、日本のものづくりに危機感を感じることもあるとか。

『単純に技術的なことだけ言うと正直日本のほうが技術力は高い、ただ日本はその技術力が活かせていない。木工に関しては合板を使う家具が今では圧倒的に主流になってしまっています。でも日本の伝統技術を振り返ると、もともとは無垢のものしかなかったはずです。それが生産性や流通を重視するあまり、ソリッドな木工が減ってしまっている。』

『無垢の木は繊維にそって方向があるので、その方向を間違うと壊れてしまう。木の性質を正しく理解して、木に無理をさせないように家具を作ります。ぼくがNIKARIで学んだのは、ソリッドのものを正しく使おう、正しく組み上げようという家具作りなんです。』

カリ・ヴィルタネンの影響を多大に受けた智士さんがデザインする家具は私たち日本人から見ればとても北欧的に見えます。しかしフィンランド人から見た智士さんのデザインは「日本的」だと言われることがあるのだそう。

『ぼくはカリ・ヴィルタネンの影響をものすごく受けているので、自分がデザインしたものはNIKARIっぽいと思っているのですが、彼らから見ると、ぼくのデザインの要素に、例えば日本の細い格子、障子とか細工の入った建具などの日本のイメージを重ねるんでしょうね。向こうは「彫る」イメージ、日本は「組む」イメージでしょうか。一昨年、両足院で椅子展をやったときにこの椅子を置いたのですが、椅子だけを見ると北欧デザインそのものなのに、とても自然に日本建築にも馴染んだんです。これはデザインが決して世界共通言語でなく、土地や民族の文化に根ざしていることを示していて、とても興味深いですよね。』

智士さんの仕事を眺めていると、“試行錯誤そのものを楽しんでいる”ように思えてきます。

合理性という言葉だけではやや無味乾燥に聞こえますが、問題解決のプロセスそのものが智士さんにとってクリエイティブの源泉になっているのは間違いありません。今回紹介できない企業秘密のアイデアを、私たちに目を輝かせてあれこれ解説してくれる様は、まるで無邪気な少年のようでした。

『いまだに一から十まで関わっていたいと思うんですよ。

なぜなら自分自身まだ完全に木工を把握しきれていないと思うから。まだ学びの途中というか。その試行錯誤がこの仕事の面白いところ。こういうものを作りたいと出されたお題に対して、悩んで工夫して解決する。

「NIKARI」のものを作り続けたいというのもこれが理由なんですよ。だから僕は自分のことを作家ではなく、一木工職人だと思っています。』

智士さんの“ 一職人でありたい”という言葉は、初心でありつづけることの大切さを心に刻み込む言葉です。

“ 作家ではなく職人であること。”

それは、朝日焼のものづくりでも全く同じことが言えることではないでしょうか。初心と熟練が決してかけ離れたものではなく、つねに表裏一体のものであることを智士さんとの会話の中で思い返したのでした。

染色:永野 美和子(Miwako Nagano)

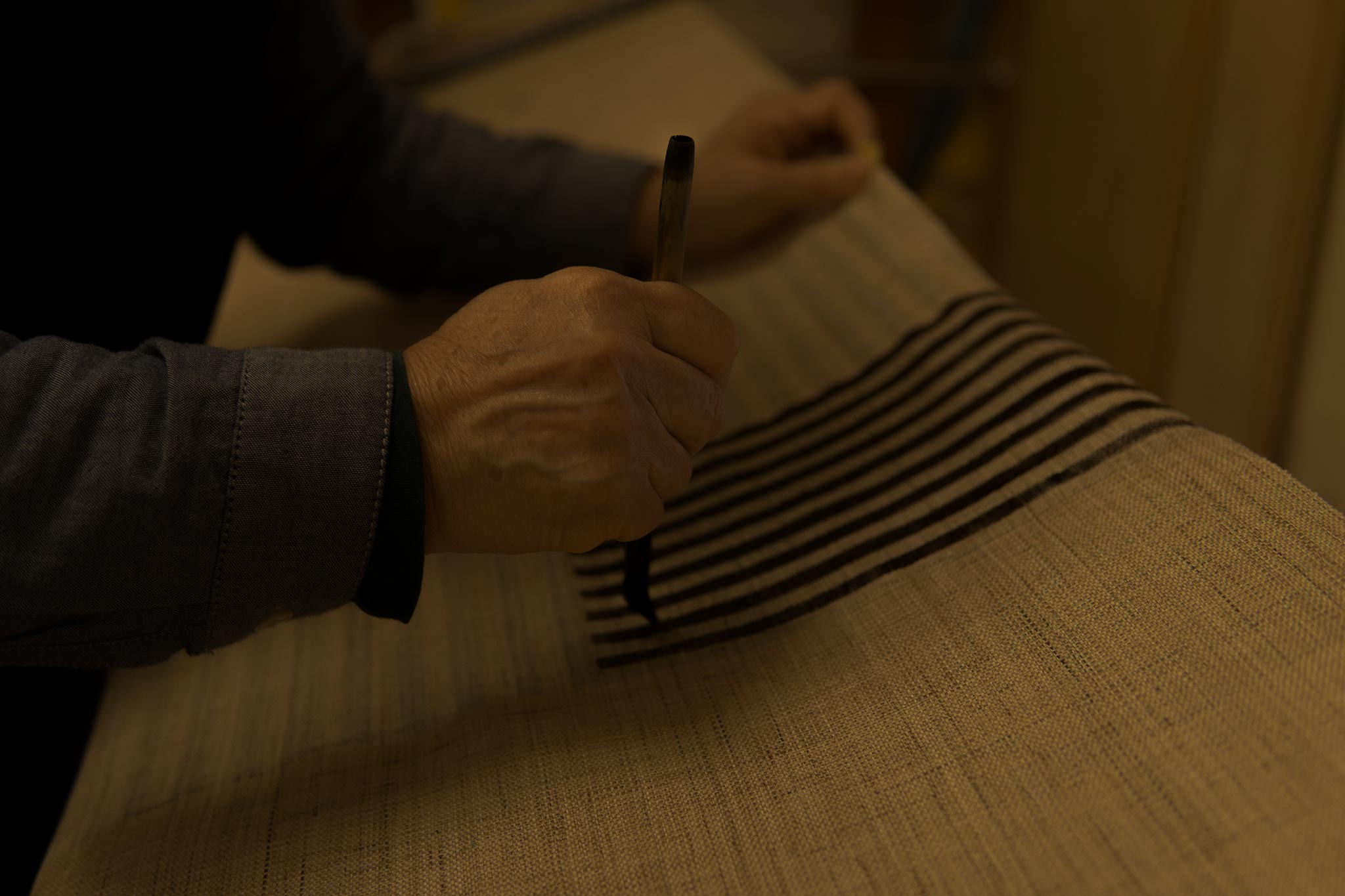

染色職人である母、美和子さんの熟練の仕事ぶりを見学していると、誰もが代々染色の仕事をしてきた家筋のように見えるかもしれません。でもお話しを聞くと、息子さんと同じくまったくの未経験からこの世界に入ったというから驚きます。

『永野染色をはじめてもう41〜2年になりますかね。

朝日焼の昔の店舗ののれんも作ったんですよ。最初に作ったのが2008年。朝日焼の先代のお父さんが私の高校の時の後輩になるんですよ。私の一つ下の主人が高校の時、山岳部に入っていましてお父さんも山岳部だったんです。』

『もともとはまったく関係のない公務員をしていたんです。でも絵を描くことが好き、織物も好き、とにかくいろんなことに興味があった。その中で何が一番、本当にしたいんや、って考えたらやっぱり筆とか鉛筆を持つ仕事がしたいと思って。それで公務員を辞めて、その時たまたま新聞で“ 友禅職人募集”の広告を見たんです。何も考えず飛びついた(笑)』

加賀友禅と京友禅の2つの会社でさまざま技術を“見て学んだ”という美和子さんでしたが、持ち前の好奇心は日増しに欲求不満に変わっていったそうで、同じことを繰り返すワンパターンな仕事にだんだんと飽きてしまいました。

“自分で色を作りたい、好きなように図案を彩色したい”。

それならば生活が多少厳しくなっても自分で始めるしかない。

こうしてたった一人の「永野染色」が誕生しました。

最初は藍染や草木染めろうけつ染など、美和子さんの好奇心の赴くままに、自分の興味があることは何でも作って試してみました。

『いろいろやってみて、その中で一番自分に合うのは糸目※を描くことでも、ろうけつでもない、ただ昔ながらの日本の独特な、型を掘って、糊を置いてそこに染色して、裏も染めて、自分で蒸して縫製して、結局全部自分でやることだったんです。』

ある時、美和子さんは麻の布を染めてみようと思い立ちました。シルクは動物性繊維、麻とか綿は植物繊維なので染料もまったく違います。最初は麻とか綿とかを染める染料すら知らなかったといいます。

『友禅系の本は山ほどあるんですよ。綿も藍染とか草木染めとかいろんな本がありますが、麻を染料を使って刷毛で染めていくノウハウを知ろうと思うとなかなか見つからない。さてどうしようか?と思いましたね。』

※糸目:柄の輪郭の白い線のこと。下絵を描いた仮絵羽を一旦解き、下絵に沿って細く糊を置いていきます。この糊が生地に染み込んで防波堤となり、染料を挿しても色が滲んで混ざり合わないようになります。

それからは独学で実験・失敗の手探りの毎日。麻に最適な染料と配分だったり、蒸し加工で色を定着するのに最適な蒸し時間だったり、いろんなことを自分で試しながら、麻の染色のノウハウを一歩一歩蓄積していきました。

『色を染めて、色が薬品反応を起こして定着する原理も、本にはあたりまえのように書いてあるんですが、「蒸し固着」に関してはさらっと書いてあるだけで詳しくは何も書いてないんです。あまり薬品は使いたくないのでその蒸し固着を私はしたいのに、肝心なことは本には書いてない。』

それまでは以前勤めていた友禅関係の専門の蒸し屋さんに外注していたそうですが、それでは試行錯誤ができない。それならばと、美和子さんは思い切って蒸し器を自前で購入してしまいました。それからは独学で蒸し固着の実験の毎日です。落ち着いた色にしようと思ってにごし色を入れた場合、蒸しすぎると色が飛んでしまって明るい色だけが残ったり、逆に暗い色だけが残ったり、意図した色を再現する法則を見つけるのは相当な根気が必要だったと言います。たまたまいい色が出たときに、その再現方法を何度も何度も繰り返すのです。

この独学の試行錯誤の日々は、やがて自己流の麻の染色技法として結実しました。全国でも珍しい麻の染色は、こうして京都宇治の小さな染色職人の手探りの試行錯誤のもとに生まれたのです。

麻の染色の魅力は何と言ってもその発色の良さです。同じ色を木綿と麻に染めたら麻のほうが一目瞭然で発色の良さに気づくでしょう。染料で染めるのでベタっとした感じがなく、両面すべてを染めているので深みが違います。

『他で麻ののれんを見かけても、顔料で絵を描いているものが多いですね。でもそれだと結局は無地の布の上にただ色が乗っているだけです。裏に色が染み込まない。私の場合は染料ですので裏に色が染み込みます。麻そのものが染まっているので、表裏どちらも美しい。麻の素材そのものの良さがでるのです。』

『麻の染色を確立したのが今の工房で働いているスタッフの一人が実験段階のときから手伝ってくれているので20年くらい前ですかね。それからはいろんな色の発色ができるようになって、それで店舗のれんの依頼がいっきに増えたんです。』

麻ののれんの難しさは、染めだけでなく図案にも苦心がありました。美和子さんの図案は驚くほどシンプル。でもそれが不思議と心地良く印象に残ります。智士さんの作る家具にも共通した日常の中で溶け込むデザイン。

『私はずっと着物の業界を見てきたので、のれんにしたら綺麗だろうと思う図案のアイデアはたくさんありました。でも実際着物の図案の一番いいところをのれんに持ってくると全然良くない。着物はたまに着るから良いのであって、毎日見るのれんでは逆に邪魔だということに気づきました。』

『それでどんどん無駄な図案を省いていったんです。これ以上削れない1点まで絞り込む。線もどんどん簡素になっていきました。一見すると誰でも描けそうな図案ですが、これでいいんです。そのシンプルさにたどり着く試行錯誤の結果ですから。私なりに淘汰したやり方なんです。』

『今は4人体制でがんばっていますが、うちには学校で技術を学んだ人が一人もいないんです。

私もそうですが、手伝ってくれている3人の職人もすべてここで一から学んで、一緒に試行錯誤して覚えていった。息子も同じですよね。

私なんかも、学校や職場で正式に教えてもらったことがなく、ほとんど見様見真似と盗み見だけで生きてきたようなものなので。失敗から学んでいくしかなかったんですね。』

『もしかしたら本当の基本というのは分かっていないのかもしれない。

昔はそれが多少なりともコンプレックスに感じたことはあります。でも今では独学で歩んできた自分の道を誇りに思っています。

独学だからここそ、その経験が生かせる。自分のものにできると思うのです。

それが職人の本当の仕事ではないでしょうか?』

価格 24,200円(税込)

フィンランドにて木工を勉強した永野製作所 永野智士氏に依頼した茶箱。煎茶器を収納する茶箱。蓋がお盆になります。日本にしか生息していない栓(せん)の木で製作し、使い込むほど木の味わいが増します。

作り手 永野製作所

サイズ w340×d135×h110 mm

素材 栓(せん)の木

塗装 オスモカラー

価格 11,000円(税込)

フィンランドにて木工を勉強した永野製作所 永野智士氏に依頼した茶盆。茶器を運ぶ際やお茶を淹れる際に使いやすい内寸が八寸(24cm)サイズの四方盆です。日本にしか生息していない栓(せん)の木で製作し、使い込むほど木の味わいが増します。

作り手 永野製作所

サイズ w240×d240×h28 mm

素材 栓(せん)の木

塗装 オスモカラー

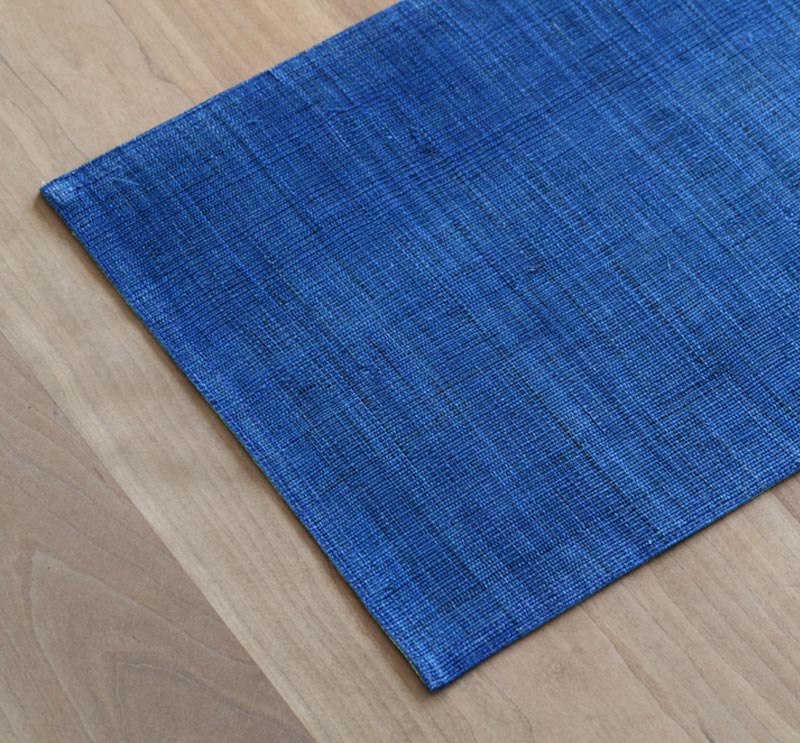

価格 3,960円(税込)

朝日焼の茶器に合わせて制作いただいたティーマット。素材は「麻(あさ)」です。 瑠璃色(濃青)と瓶覗色(薄青緑)の二色を重ねて縫製(ほうせい)しておりますので、その時々の雰囲気でお互いの色を楽しんでいただけます。

作り手 永野染色

サイズ 430×280×h1.5 mm

素材 麻 生平(きびら)

地色 片面・瑠璃(るり)色

片面・瓶覗(かめのぞき)色

染料 反応染料

色止め 有

撥水加工 有

仕立 袋縫

限定商品 80枚(一反のみの制作)